What are Shin Splints ?

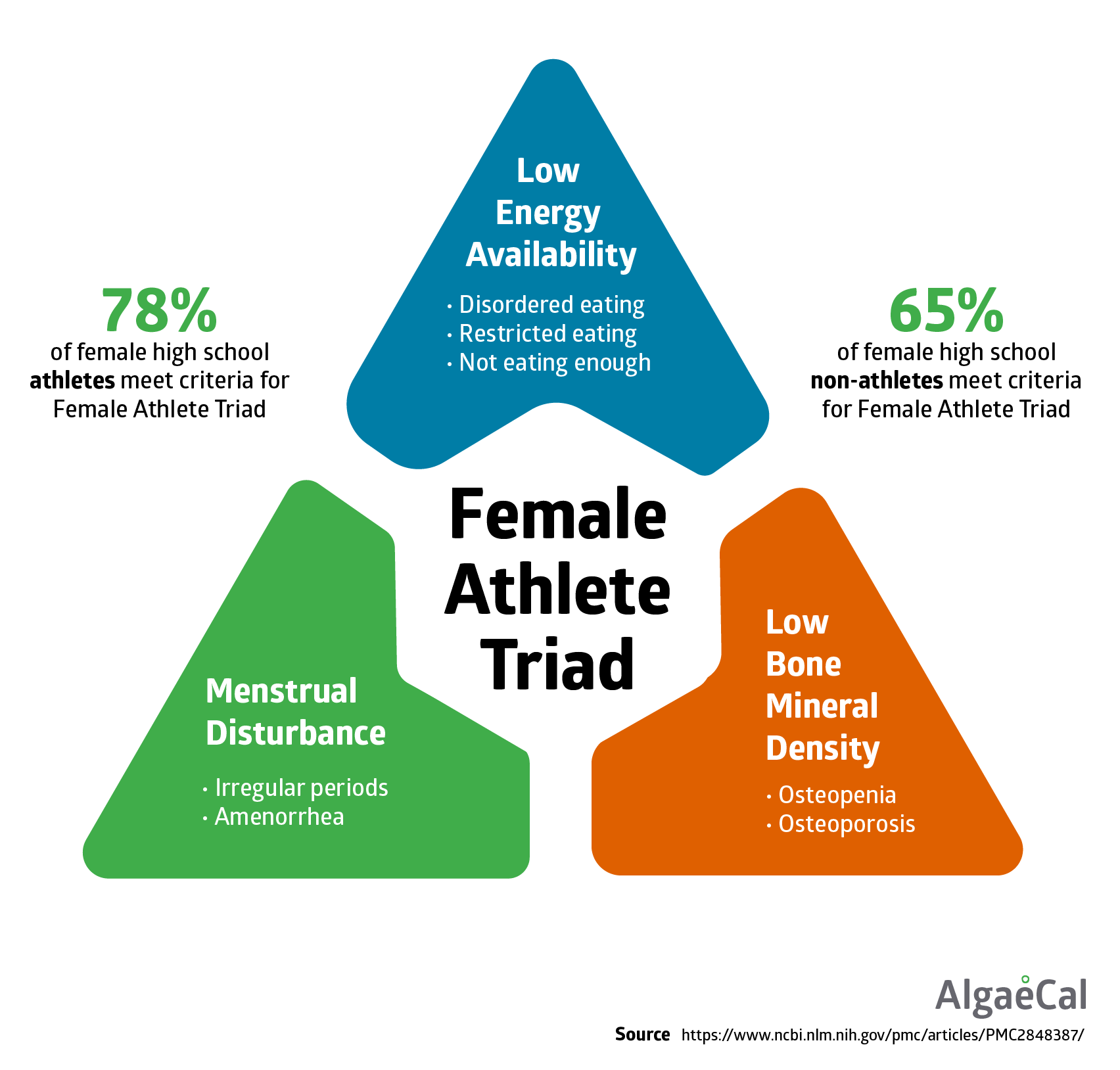

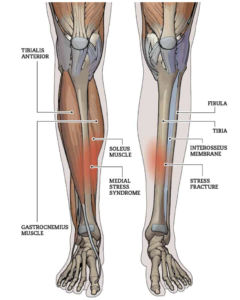

Generally anytime we get pain in the shins, typically when associated when running there’s a tendency to label it as “shin splints” but what does that actually mean? When people say “shin splints” what they’re usually referring to is “medial tibial stress syndrome” or “MTSS” for short:

Medial = inner

Tibial = pain weight-bearing shin bone

Image source: Solushin.com

What causes the pain ?

According to the latest research MTSS may be due to a build up of micro-damage of the shin bone based on bone biopsies (Winters et al, 2018).

There may be inflammation of the periosteum (the outer layer of the bone) due to repeated/excessive traction of the muscles that attach to it (tibialis posterior / soleus). Your periosteum is highly innervated meaning it has a lot of nerve supply so can generate a lot of pain. If you’ve ever walked into a coffee table, been kicked in the shin on missed a box jump, you know this is true!

Who tends to get shin splints ?

- Long distance runners / New runners

- Military / New recruits

- Dancers / Gymnasts

Given that shin splints is essentially a bone stress injury it probably won’t come as much surprise that the people who tend to get it are those involved in repetitive high impact activities: military, runners, dancers (Lohrer et al 2018). It’s very common that people who have either just started running or have had a prolonged period off and jump back in are very prone to developing this. This is mainly because bone (just like muscle) remodels according to the “if you don’t use it, you lose it” principle. The muscles that help absorb shock and take the stress off the bones/joints get weaker overtime as does the bone itself. I had a patient who hadn’t run at all for 6 months and then suddenly tried running 2 x 5km in the week + 10km on the weekend and was ramping up towards a marathon. Both his shins said “nah”

Image source: Healthline

How is it diagnosed ?

Generally this is an injury that can be diagnosed from the description of the symptoms and a physical examination and does not require a scan (Winters et al, 2018)

- Exercise induced pain over the lower 2/3rds of the inner aspect of the shin

- Tender the touch over this area that typically spans 5cm or more

What else could it be ?

There are two main conditions you want to make sure this is NOT:

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

- Cramping/burning

- Pressure like pain in the calf

- Pins & Needles +/-

- Foot going cold and or pale, reducing and/or faint pulses (dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial)

- Induced by exercise which return to normal with rest

Image source: SEMS journal

Tibial stress fracture

- Well localised pain on the bone (in an area <5cm)

- The 3 areas there can occur:

- 1) Anterior tibia (front of the shin) high risk

- 2) Medial malleolus (lump on the inside of your ankle) high risk

- 3) Posteromedial tibia (inside and round the back of the shin) low risk

- Crescendo pain pattern i.e. symptoms progressively get worse the longer you continue running

- There may be night pain and/or pain at rest

Image source: Advancedosm.com

Some stress fractures are classed as “high risk” meaning they have a greater chance of progressing to a full fracture if mismanaged and don’t heal as easily. You can see the posteromedial tibia is classed as low risk and this is because it has a better blood supply. The medial malleolus and anterior tibia are classed as high risk sites and need to be managed accordingly.

Hop test: The Single Leg Hop test has a strong ability to rule out a stress fracture. In other words if you can perform the hop test pain-free you almost certainly do NOT have a stress fracture. If you do have pain when hopping however this test cannot specify that the cause is definitely a stress fracture (Milgram et al 2020)

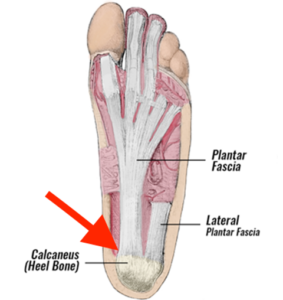

Who is more at risk of stress fractures ?

Stress fractures aren’t just diagnosed by symptoms. Some people will have already “set the stage” for a stress fracture to be more likely to occur (unintentionally of course). Here are some questions to ask yourself to assess whether you are at a higher risk of developing a stress fracture:

- Is your BMI below < 19?

- Can you recall any gaps/irregularity in your menstrual cycle over the past 12 months?

- Are you peri/post menopausal?

- Have you been diagnosed with an eating disorder?

- Are you following a specific diet e.g. calorie restriction, vegan, vegetarian?

- Have you been taking long-term medications e.g. steroids (prednisolone for example)?

- Spike in training volume/mileage?

- Vitamin D deficiency?

This is not an exhaustive list but the more of these questions you’re answering “yes” to, the more at risk you are of developing a stress fracture. If you’re interested in finding out more about this topic there is a good article and infographic on the British Journal of Sports Medicine website HERE

What should I do ?

The main principle here is that we need to reduce load going through the bone for a period to allow it to repair. If it’s a stable / low risk stress fracture and you can walk pain-free it may be that you will just need to have a period off running but won’t necessarily need to be immobilized or offloaded. If walking is painful you may need to be put in an aircast boot for a period and offloaded before returning to low load activities. In addition any causative factors e.g. vitamin D, hormone deficiencies etc any bone health issues need to addressed.

- Start a graded loading program supervised by a qualified professional

- Make sure you keep it pain-free

- Find an appropriate starting point (impact tolerance test e.g. two foot hopping, jogging on the spot, single leg hopping etc)

- You would run through this as guided by your therapist to determine what your starting point would be when it comes to loading.

- When the pain starts the test stops.

- Example: 1-2 minutes pain-free jogging on the spot in 2-3 x per day (separated by 4-8 hours of rest)

- Incorporate strength work for: the calf muscles (gastroc/soleus); quads; glutes

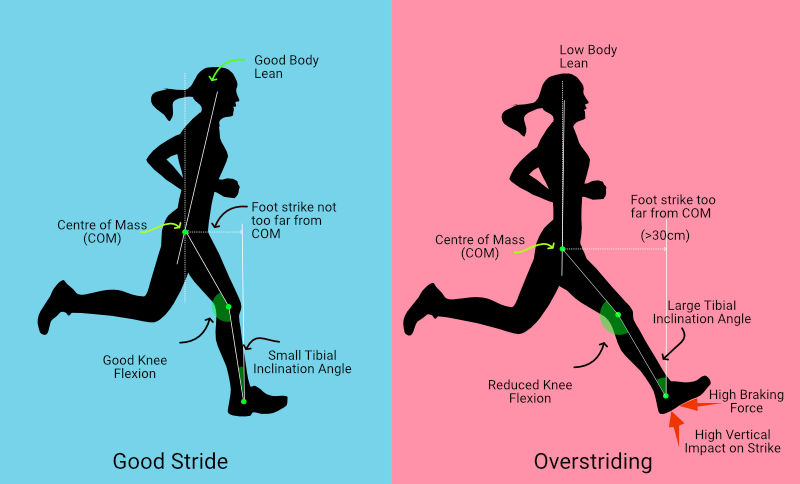

- Assess & Address your cadence (steps per minute). Research by Luedke et al (2016) showed that cadence around 165 steps per min of below increases your risk of developing shin pain while a cadence of 174 or higher reduces it. You can download a run cadence app this THIS one to test.

- Prioritize rest & recovery e.g. sufficient high quality sleep; nutrition

Research shows that the “little and often” approach is more effective specifically when it comes to stimulating bone remodeling (Turner & Robling, 2005)

Why strengthen?

The rationale for calf strengthening is that is helps with the shock absorption thereby reducing the bending forces through the bone that are linked with the onset of pain. Weight-bearing exercises in general are also going to stimulate the bone to reinforce itself (stimulates osteoblast activity if you want the geeky explanation).

- Reduced ankle plantarflexion endurance aka poor calf endurance (Madeley et al, 2007)

- The soleus is one of the two main calf muscles that makes up 52% of calf bulk (Albracht et al, 2008) and manages up to 7-8 x bodyweight during vs 1.2 – 3 x bodyweight that the gastroc handles (Almonroeder et al 2013)

Image source: Wikipedia

NB: This study was based on a sample of 566 healthy people ranging from 21-81 years old performing a single leg heel raise on a 10 degree incline performing them at a fixed pace with a metronome. Results are going to be influenced by multiple factors such as gender, age, BMI, fitness levels etc.

What shouldn’t I do ?

- DON’T:

- Ignore it and continue to run through symptoms

- AVOID:

- Narrow step width

- Over striding

- Running “loudly”

Image source: Geeks on Feet

Narrow feet is more likely to cause ankles to roll in aka eversion and hip adduction which have been linked with increased shin (tibial) loading and development of stress fractures (Meardon et al 2014)

Decreasing stride length reduces tibial loading (Hobara et al, 2012) (Edwards et al, 2009)

Landing more “softly” is associated with less impact forces (Crowell & Davis, 2011)

When can I return to running ?

Unfortunately there is no specific one-size fits all answer to this question.

As a general guide I suggest you meet the follow criteria before you attempt a return to run:

1) Walk 10,000 steps pain-free

2) Able to jog on the spot for 60 seconds minimum pain-free

3) Able to single leg hop for 30 seconds minimum pain-free

If you can achieve all these criteria you may be able to begin to introduce short runs e.g. 2-5 minutes (as guided by your therapist).

Need some help ?

If you’re not sure what to do this is something I’d recommend booking a consultation for so we can take a thorough history and talk you through the next steps whether that be a referral for imaging or rehab.

You can easily book a consultation with me HERE

Take care of yourselves!

Jay

MSc Physiotherapist MCSP, HCPC